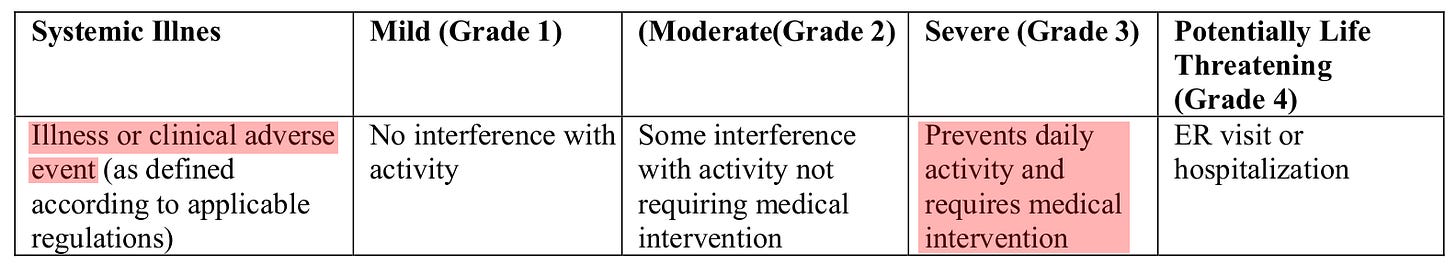

Is it worse if twelve people have severe adverse vaccine events or one person has severe COVID-19? I’m not a doctor and none of this should be taken as medical advice, but people generally want to avoid severe medical outcomes. In both cases, severe means “prevents daily activity and requires medical intervention” (see also the notes below).

These FDA definitions are written primarily from the patient’s perspective and hospital administrators are likely to think differently. For example, a patient may rate certain heart problems as worse than COVID-19 while they are routine and profitable matters for hospitals, but COVID-19 presents enormous infection-control and economic difficulties. Natural immunity, which reduces the benefit of vaccination, is of significant value to individuals, but for health administrators it is one more thing to keep track of.

Pfizer’s BNT162b2 vaccine is widely used to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and has been deemed safe by government agencies and medical experts. What does the safety study say? The main text describes some aspects of the adverse event rate while the study’s supplementary appendix includes important numbers. Of particular note (see Table S3, reproduced below) are the 240 severe adverse events in the vaccine group compared to 139 for the placebo, which can be considered the background rate. The difference of 101 is too large to be a statistical fluke (physicists would call it a 5-sigma effect), and the trial’s randomization leads to the conclusion that approximately this many excess events were indeed the result of vaccination. [Update: Pfizer data are of questionable integrity.]

The vaccine’s adverse event excess can be compared to the reduction in COVID-19 cases. During the two month surveillance window, vaccine recipients had one case of severe COVID-19 while placebo recipients had 9 (see Table S5). If the vaccine causes 101/(9-1) = 12.6 severe adverse events for every severe COVID-19 case prevented, is that a net benefit?

Note on severity: Some MDs have said that of course severe COVID-19 is worse than a severe adverse event. But the claim was never justified and it directly contradicts the definitions in the first table at the top. These MDs often mention respiratory failure, which would be considered critical rather than severe COVID-19 (see below), and was too rare to be seen in Pfizer’s RCT. There is no line for critical COVID-19 in the study tables.

While the initial safety study used a broad definition of “severe COVID-19” (pages 373-374) that could have included critical cases, the definition did not require the cases to be critical. The subsequent follow-up study twice cites the FDA’s definition that specifically excludes the critical (i.e. life-threatening) category. One can only conclude that none of the severe cases were critical, as the follow-up study’s cases are a superset of the initial cases and, despite the change of definitions, no line for critical COVID-19 was added.

FDA definitions:

In terms of specific criteria, HR ≥ 125 for severe COVID-19 is less stringent than HR ≥ 130 for a tachycardia adverse event to rate as severe, and SpO₂ < 93 % is not uncommon among older adults without COVID-19.

Note on updated study: The broader definition of severe COVID-19 was abandoned in the updated paper, which cites the FDA definition. But the large mismatch in observation windows for safety vs. efficacy makes it unclear if the new ratio of severe outcomes (3.9) is more appropriate than the earlier ratio of 12.6.

Technical note on statistical significance: Approximating the observed severe adverse event frequencies as Poisson random variables yields individual variances that equal the means (240 and 139), and the variance of their difference is the sum of the variances. The difference (101) is then over five times the standard deviation of sqrt(240+139)=19.5. Such a significant result is exceedingly unlikely to occur by chance.

A more precise calculation in R validates this conclusion (note the small p-value).

> severe <- c(240, 139)

> n <- c(21621, 21631)

> prop.test(severe, n)

2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction

data: severe out of n

X-squared = 26.665, df = 1, p-value = 2.419e-07

alternative hypothesis: two.sided

95 percent confidence interval:

0.002871931 0.006476782

sample estimates:

prop 1 prop 2

0.011100319 0.006425963From time to time, I edit and update this article.

Please keep any comments on topic.

One way I tried to explain "severe" and "serious" adverse events to the general reader was this way:

<snip>

"Severe adverse event” [is] anything that interferes with normal function. That includes things like, you got a headache and so you didn’t cook dinner as you normally would, or you called off work for a day or two because you had a fever (as many people were told to expect).

Which sounds scarier?

“I got the Pfizer vaccine, and I had a severe adverse event.”

Or

“I got the Pfizer vaccine, and I had a fever and stayed home for a day.”

These are equivalent. In other words, a severe adverse event is not the scary thing that it sounds like.

Same for the “serious” adverse events, which ...resulted in a hospital trip. There were 127 people in the Pfizer group and 116 people in the placebo group who ended up taking a trip to the hospital. We know that in clinical trials, there’s very much a bias toward “When in doubt, go to the hospital” because the patients’ safety is paramount.

But we know, don’t we, that the 116 people in the placebo group who went to the hospital had a tiny amount of salt water in their arms and there was absolutely nothing seriously wrong with them [related to the shot], right? Common sense. So 116 people went to the hospital because they had some kind of random symptom unrelated to the salt water, were scared, and everyone erred on the side of caution.

It's reasonable to suppose, human nature being what it is, and random symptoms being what they are, that a similar number of people who received the Pfizer vaccine also had some kind of random symptom unrelated to their injection, were scared, and everyone erred on the side of caution with them too. Probably in the neighborhood of …116, like the other group.

So then the question becomes: if 127 in the Pfizer group went to the hospital, versus 116 in the placebo group, is that 11-person difference between groups, in the context of 46,331 people total in the Pfizer trial, a statistically significant difference? Without doing the statistics, I’m going to guess “probably not.”

What is clear, at the very least, is that people were not experiencing effects from the vaccine bad enough to send them to the hospital, any more than they were experiencing bad effects from the salt-water placebo that sent them to the hospital.

<end snip>

It's really a problem with language and communication isn't it? People who are fearful of the vaccine are going to hear the words "serious adverse event" and not even know what those words mean, and certainly they won't know what the numbers mean in context, or what they represent. Our big-name science communicators have done a terrible job conveying information to the public.

We can take preventative measures to improve chances of less severe Covid. Improve our health and take vitamins.

But the injections, why Russian Roulette oneself with them, and live in sick fear of unknown tinkering long term. Being healthy won't save one from the clot shot.